It ain’t quite a British Bulldog, but the Hesketh motorcycle still demands respect. Despite near-fatal flaws and fiscal foolishness, it simply refused to lay down and die…

‘This bike is a giant. It’s going to become a classic’ –

Superbike magazine, June 1980

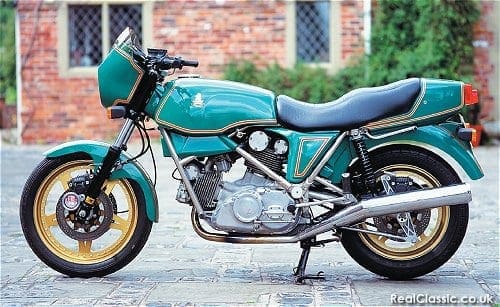

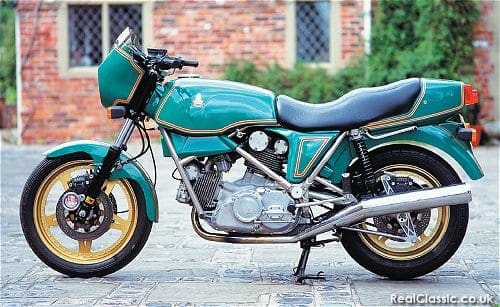

They were so right – but not immediately. When the Hesketh V1000 first hit the road in 1981 it was hardly what the world had been waiting for. Less than 150 were built before the company went bust. A successor picked up the pieces – and went under just as fast. But the Hesketh motorcycle always had great potential and it was always inspirational. It inspired a loyal following among the bike’s owners, and it inspired the development team to stick with it, finish the job and now take it even further with a new bike for 2004. Today you can buy a brand new, bespoke V1000, Vampire, Vortan or even the latest 1200cc version. The prices don’t even look too frightening compared to an MV Agusta or Benelli dreambike. But back in the 1970s, Lord Thomas Alexander Fermor-Hesketh hoped to revitalise an industry, and in that aim he most certainly did not succeed.

Enjoy more RealClassic reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Lord Hesketh always had an automotive involvement, although he didn’t actually hold a bike licence (and failed his test more than once). He’d been playing around with a Formula One car racing team and had an R&D and engineering facility tucked away in the grounds of his estate at Easton Neston in the English heartland. You can just picture it; a treelined driveway, cucumber sandwiches on the terrace, croquet on the lovingly prepared lawns, and a V8 racing engine howling away at full bore in the background… Anyway, Hesketh needed to spend less money than his F1 ambitions were costing him, and wanted to put his engineering people to good use. Diversification was the key – and Hesketh chose motorcycles.

Together with his business partner, AG ‘Bubbles’ Horsley, Hesketh had a patriotic yearning to rejuvenate the fading British motorcycle industry. He wanted to build a bike with character, one which wasn’t in any way an Oriental UJM. The Hesketh was to be a prestige project to build a modern Vincent or Brough Superior, an exclusive, sporting gentleman’s motorcycle. The British bike press fell over themselves in a self-indulgent frenzy when it became known that a member of the English aristocracy was going to build a new British motorcycle. They loved the idea (but they would come to hate the reality). What the world didn’t know when Hesketh started his foray into motorcycling was that his F1 enterprise had just dropped £1million (that was a lot of dosh back in the 1970s), and there was no sound financial footing for the bike business to build upon.

Still, the global bike business was booming then, even if the British end had tied itself in knots. With Triumph flailing around in a fit of selfflagellation, there was a definite niche for a quality British bike – if Hesketh was quick he might be able to plug that gap.

Red is better… Hesketh V1000

The above statement is a true thing but, oh boy, in its initial form the V1000 was home to a whole gaggle of gremlins. In building it, Hesketh brought his car contacts and engineers into play – which was the whole point of the exercise, although it was this first, flawed footing which ultimately doomed the whole enterprise. Motor car engineering concepts have been very successfully transferred to motorcycles, but it has to be done carefully and sympathetically. Hesketh was pushed for time. It was 1978 and he wanted to sell a customer motorcycle in the first year of the next decade.

The engine brief went to Weslake, the well-respected British engineering consultants with whom Hesketh had worked in F1, and it included some very specific requirements. The motor had to be a V-twin, it was supposed to be shaft-drive, and some car-oriented concerns meant that Weslake’s designer was constrained and compromised elsewhere in what he could do. Even so, you’ve got to admire his efforts.

The result was an impressive monster of a motor. An 85- horsepower, 992cc dohc, 4-valve per head, 90-degree L-twin which weighed over 200lb all on its ownsome. It appeared to owe something to Ducati in its configuration, but this powerplant was built for long legs and longevity instead of sudden spurts of speed. It was the sort of motor you might employ to move a small mountain rather than a mere motorcycle. It might well have done the job without a hitch if attached to the intended shaft drive – but the shaftdrive idea had to be abandoned when BMW took a patent action against Yamaha over their drive design.

Immense solidity of engine makes massive frame look spindly… Hesketh V1000 Rear Cylinder

The Hesketh final transmission was too similar to BMW’s for comfort, so it had to be dropped and the switch was made to chain drive. The gearbox, of course, was designed for a shaft-drive motorcycle and the loadings all changed – meanwhile, the only engine sprocket they could find to fit the available space was a 13-tooth item which messed up the gearing. In all this confusion, and given the massive pinions which the gearbox employed, transmission snatch was an inevitable gremlin which took up residence in its stately home. Perhaps at this point it would have been more prudent to stop, re-engineer the design, and cut out some of the compromises. When you’re reinventing the wheel, perhaps you need to take it at a steady pace!

But Hesketh was desperately short of time, running low on funds, and the media were clamouring to see the motorcycle he’d been promising them. Work went on. John Mockett, who’d styled bikes for Yamaha and subsequently penned the looks of the original Hinckley Triumph range, designed the V1000’s look and feel. Mick Broom, a well qualified mechanical engineer and successful racer, became the Hesketh test rider and later the mainstay of the engine’s development. It’s Mick who has kept the faith with the Hesketh project, and it’s Mick who has refined the reality into the latest 1200cc format. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. The Vee was housed in a nickelplated duplex parallelogram frame made of Reynolds 531 tubing, triangulated at every available opportunity to manage the mass of the motor (it used the engine as a stressed member of the chassis, much like a Vincent).

Hesketh had originally hoped to use only British components but, when that proved impossible, 36mm Dell’Orto carbs, 38mm Marzocchi forks and 11-inch Brembo disc brakes were specified. Five-way adjustable Girling gas shocks originally cushioned the rear end although these were supplanted by Marzocchi items, too. Astralite alloy wheels – the rear a new, specially-developed 17-inch size – carried the very first V-rated Avon Venom tyres. Overall, the V1000 was a mightily impressive package, and very splendid it looked, too, in its aristocratic scarlet livery. (But as befits a hand-built bike the customer could specify any colour he chose, and the owners of both the V1000 and Vampire seen here chose green. Mick Broom’s racing colours were green, and it’s his favourite shade, so now you know why not all Heskeths are red!).

Marzocchi shocks, Brembo brakes, Astralite wheels… Hesketh V1000 Rear Wheel

The V1000 looked great. But sooner or later the press and public were going to have to ride it. And the truth is, the press rode it long before it was really finished. And they didn’t like what they found.

The Hesketh factory officially opened on the 12th of August 1981, and the hacks were let loose on the V1000s the next day. In order to set up the assembly line and its 70 staff, Lord Hesketh had needed to raise finance from the stock market – he had originally hoped to engage the interest of an existing automotive manufacturer but none could be tempted. The factory was expected to build 500 bikes in its first year, which would be delivered to 25 dealers around the UK, and then production would rise to 2000 bikes in 1982. That was the plan…

…until the bikes were actually ridden. The journalists, now used to extremely well-polished machines pouring out of Japan, were vocal in their disapproval of the V1000’s rough edges. It was criticised for being slow, noisy, too thirsty, too tall, too expensive, and possessed of possibly the least pleasant gearchange mechanism on the planet, together with whiplashinducing transmission snatch.

Almost everyone could find something positive to say about the V1000, but absolutely everyone had something bad to say about it, too. The development team scuttled back to the drawing board to try to evict some of the growing band of gremlins.

By the end of 1981 the production line still wasn’t running.

On top of all the obvious problems which made themselves instantly apparent, more causes for concern kept appearing as the test bikes clocked up the miles. There’s nothing unusual about this – it’s a standard part of the development process – but in the Hesketh’s case it was all being done in the public eye. And there had been some very strange decisions made earlier in the machine’s evolution. For instance, the 38-piece centrestands cost over £100 each but the expensive Mahle pistons, which were needed to keep noise and wear under control, were jettisoned in favour of bulkbought econo-model Hepolite items.

Likewise, a lack of communication between the R&D department and the under-employed factory led to all sorts of specification and sourcing foul-ups – the cam shims could have been sourced from a Triumph car at a cost of 7pence each. Instead, identical items were built especially for Hesketh at 70pence apiece – 10 times the cost! The factory was put onto short time while solutions were sought for all manner of under-specification and quality problems (poor castings, porous crankcases, dodgy head race bearings, etc), but the money was running out.

In the spring of 1982 the first customer bikes were finally delivered. Many of the initial, supremely patient buyers proved to be amazingly tolerant of their machine’s teething troubles. These included multiple engine replacements and continual oil leaks, plus appalling mechanical noise and a gearchange which would still frighten many a fragile foot. These owners had paid handsomely for the V1000s: the hoped-for economies of scale never arrived and so the bikes were sold for around £4500, and then £4995 – over twice the price of a Moto Guzzi Le Mans, Ducati 900 or Yamaha TR1.

Meanwhile, the general economic gloom of the 1980s got a grip, and the Hesketh company’s share price fell faster than most when it became apparent that this luxury motorcycle really wasn’t up to much. With the press coverage becoming all the more critical, the Hesketh share value plummeted and trading was finally suspended. When the dust settled on the defunct company, 139 V1000 bikes had been built. The Hesketh company had debts of over £4,000,000.

But it wasn’t all over, not by a long chalk. Many of the development team felt that too much progress had been made for the venture to fall at this point, and so a new company, Hesleydon, was set up. Hesleydon bought most of the rights and equipment of the old Hesketh business, was backed by Lord Hesketh himself, and was led by Mick Broom who became the new company’s product development manager. Hesleydon set up business back at Hesketh’s R&D shop at Easton Neston and set about curing some of the V1000’s ills with the EN10 package of modifications.

Mick Broom’s team worked hard to stabilise the oil pressure and improve gear selection, swapped to new main bearings which wouldn’t turn in their housings (ouch), and added a camchain ‘sock’ to cure the leak around the joint where the camchain case met the crankcase. Much of this work was already in hand, said Broom; ‘When the first production machines came off the line we were already a year ahead of them with the development. But it couldn’t be implemented at the factory due to financial constraints and the pressure to get the bikes out.’

Hard to find an angle where the Vampire looks good… Hesketh V1000 and Vampire

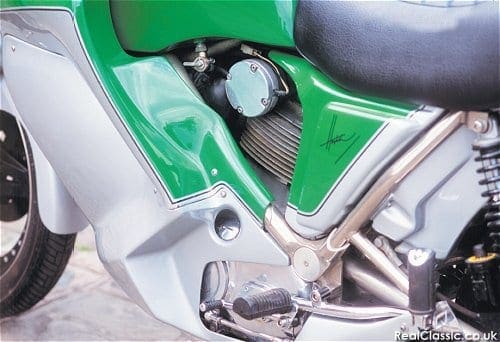

These modifications could be retro-fitted to existing V1000s, and formed the basis for the next model – the Vampire. You see, although their bikes were troublesome and quirky, the V1000 owners liked them well enough. They liked them so much that they wanted to take them touring, and they wanted a touring version with a full fairing. So Hesleydon commissioned John Mockett once again, this time to turn the V1000 into a grand tourer, and the 1984 Vampire was the result.

Again, the Vampire was a mixed bag – it only just scraped through noise regulations and still suffered from a ponderous gear-shift. It struggled to match the all-round competence of BMW’s tourers and again attracted bitter comment from the now-sour UK press. The Hesketh brand was almost beyond repair, despite the progress that Hesleydon had made. Eventually, that company also folded its tents and faded away, having made less than 50 more Hesketh bikes. But Mick Broom didn’t give up and, more than two decades after the Hesketh adventure first began, he’s still developing and still building V1000 and Vampire bikes.

Who’s been writing on my bike?… Hesketh V1000 Vampire

To mark the big twins’ 20th birthday Broom added a third model, the outlandish Vortan, and the spring of 2004 sees another landmark: the 1200cc version. All models benefit from years of development to both engine and chassis, and Broom will happily upgrade earlier bikes to the current specification where possible. After many years working on the powertrain, he more recently turned his attention to the cycle parts and beefed up the forks to 38mm to handle modern radial tyres, improved the brakes with a pair of fully-floating 300mm front stoppers, and removed 5kg of unmanageable mass from the wheels. So the 21st century Hesketh can offer a safer and more comfortable ride than the original ever did.

If you’d like one built then the cost doesn’t seem altogether too unreasonable; £11,750 will pay for the base model V1000 while the new 1200 will be a shade more expensive (you have to sort out single vehicle type approval and the legal niceties yourself). But would you really want to own and ride a Hesketh these days? After all, it doesn’t seem to have too great a track record, now does it?

Words: Rowena Hoseason Photos: Bob Clarke

Advert

Enjoy more RealClassic reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more RealClassic reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.