The very last production T160 Tridents were several hundred built to Police spec for Saudi Arabia. Steve Wilson rode a refurbished one with less than 30 miles on its clock…

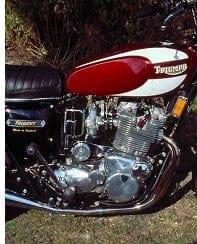

It looked like a very smart but pretty stock sort of T160 Trident, big and handsome with the 4.8 gallon tank in Cherokee Red and Cold White. Until you checked the mileage, and saw the ‘00024’ (although the trip mileometer, confusingly, read 026!). Yep, this was a Trident with a difference.

Its keeper at the time I rode it was Mark Hume, no stranger to T160s or indeed to Triumphs. His first bike had been a T120 Bonneville, bought six months old in 1973, and he knows the twins inside out. Alongside the T160 he also owned a T100, but his best-ever twin was another oil-in-frame 650, bought at Beaulieu for £340, and fitted with a 750 Morgo conversion and a single carb, which carried him both to work and on holidays for six or seven years.

‘But my trouble is, I like anything’ laughed Mark, who also owned a Moto Guzzi Le Mans Mk1. It was on another foreigner, a BMW RS, that a rear tyre blew at 90mph. The subsequent get-off laid Mark up for six months with, among other things, two crushed vertebrae and a ruptured kidney. It didn’t put him off riding, however! Perhaps it all stems from Mark’s father who ran a bathtub Triumph 5TA when he was young. Mark is currently also looking after his dad’s last bike, a Matchless G12 De Luxe 650 twin.

As a Triumph man Mark had always badly wanted a T160, but when one came up there was a serious problem. Mark was engaged at the time and the lady told him it was the Triumph or her. Errrr… no contest. Mark called a mate with a van to move him out and shortly afterwards bought the T160.

Luckily Mark’s eventual wife, Mary, is a good deal more understanding about the bikes than his previous fiancée!

On that T160 Mark put in 83,000 fast miles, but they were punctuated by two major engine blow-ups. Mark blamed himself: ‘I fitted race cams and 11:1 pistons, and I abused it. By the end it got a bit tired,’ he added, probably with some understatement. There were penalties; once it had got out of tune in that spec the Triumph would sometimes return just 18 miles to the gallon…

On that T160 Mark put in 83,000 fast miles, but they were punctuated by two major engine blow-ups. Mark blamed himself: ‘I fitted race cams and 11:1 pistons, and I abused it. By the end it got a bit tired,’ he added, probably with some understatement. There were penalties; once it had got out of tune in that spec the Triumph would sometimes return just 18 miles to the gallon…

Mark took the T160 off the road and was contemplating transforming it into a Slippery Sam replica, when he heard about the Cardinal. It was the very last, apart from his personal mount, of 11 Cardinals belonging to Ron Moss, the service engineer whom NVT had arranged to live in Saudi for a couple of years at the end of the 1970s and look after the more than 400 police T160 Cardinals there.

But how, over two decades previously, had a fast roadster like the T160 ended up as a Noddy bike in the desert? The story was convoluted. Norton Villiers Triumph’s ace police bike salesman, Neale Shilton, had cut the original deal with Prince Aziz, the Saudi Defence Minister, on a one-man mission to Riyadh in March 1975. The flamboyant Shilton, with blue lamps flashing and two-tone horns blaring, had impressed the Prince at a military tattoo by riding past the Royal enclosure, standing to attention on the footrests and giving a Sandhurst eyes-right salute!

But his demonstration mount had been a Mk3 Norton 850 Interpol Commando, and the £1million contract with which he had returned to Britain had been for Interpols. Even the Norton twins were not exactly ideal for the desert work, as Shilton had discovered when he had been forced to cut away much fibreglass from the Interpol’s fairing after the engine had run too hot in the Saudi temperatures.

At any rate, events intervened; in the summer of 1975, NVT — already embroiled with the Meriden Triumph co-op — were forced into voluntary liquidation and the Wolverhampton works, where Commandos were then being made, also became the object of a worker’s sit-in.

So the only machine NVT could offer to meet the Saudi Defence Force order for nearly 600 motorcycles were the remaining T160 Tridents being made at the former BSA factory at Small Heath. If ever a machine could have been justified in having an identity crisis it was the T160; the first Cardinals went out to Saudi badged as Nortons, while what was intended to be the last T160 produced ended up coming off the line fitted by the still-proud Small Heath workers with BSA badges!

So the only machine NVT could offer to meet the Saudi Defence Force order for nearly 600 motorcycles were the remaining T160 Tridents being made at the former BSA factory at Small Heath. If ever a machine could have been justified in having an identity crisis it was the T160; the first Cardinals went out to Saudi badged as Nortons, while what was intended to be the last T160 produced ended up coming off the line fitted by the still-proud Small Heath workers with BSA badges!

Once in Saudi, the Cardinals suffered from the fact that the police riders there had apparently not been properly trained as motorcyclists, let alone schooled in the subtleties and limitations of British bikes. The country was also newly awash with oil money, and this encouraged a casual attitude to the now abundantly available consumer durables. Accustomed to Hondas with reliable electric starting which didn’t need the throttle pumping as the button was pushed, when the T160’s borderline electric foot ran out of juice after a few stabs of the button many machines were abandoned for that reason alone, with only nominal mileage covered. Even a snapped clutch cable was enough for a bike to be discarded. Hence the very low mileages of many of the Cardinals eventually recovered from Saudi.

|

A further batch of 130 machines were never despatched, and were sold off by NVT in the UK during 1977. Mark Hume didn’t hang about. 24 hours after he had bought the Cardinal he had the engine out and the frame was on its way to be powder-coated. When he lifted the T160’s the condition of the internals told him that the engine was in fact brand new. Oil in the sump indicated that a PDI had been carried out, but that was all. In the light of all this Mark shelved his ideas about a Slippery Sam replica; this T160 was going to be a fast tourer. For that reason he stayed with the 8.25:1 compression which the Cardinals had soon adopted. Cosmetics were attended to. As well as the frame, the all-white Cardinal tank, which had gone rather yellow, was repainted by a friend. The exhaust pipes were replaced with stainless, but the brand new original silencers were retained, as were the new Girling rear shocks. The high Cardinal bars, with solid rather than Metalastic rubber-mounting bushes because of the Tri-Point windscreen fitted to the police bikes, were kept, but their fasteners like most of the rest also became stainless. One further non-standard indulgence was to have the black air-boxes chromed. Other than that, Mark’s object for his brand new engined Trident was simply, where necessary, ‘to upgrade it for today’s road.’ |

He already had a double disc fork leg, so to create a twin disc front end he took the disc off the rear brake and machined both it and the front one down from 254mm to 250mm, so that they would take Grimeca calipers rather than the original Lockheeds. Trevor Gleadall of LP Williams was selling the Grimecas for around £45, half the price of the Lockheed equivalent and, with Aeroquip hoses, just as good.

(There’s a rightness to this bike being revitalised with the help of LP Williams, as it was that firm’s founder, triple guru Les Williams, who had first accompanied Ron Moss out to Saudi and taught Ron his way round Tridents).

New master cylinders were fitted both front and rear, for the new disc there. Alloy rims and stainless steel spokes went on the wheels, with the back one reduced from the standard 19-inch to 18. For tyres, Mark favoured Avon Roadrunners, AM21 front, AM20 rear.

Mark understood that the Cardinals had one tooth less than the standard 19-tooth gearbox sprocket, to gear down for convoy duties, etc. To give himself some room for relatively easy adjustment of the ratios, Mark went to John Anderson of Performance Motorcycles (yes, the man who cured Frank the ex-editor’s smoking T160), for the aluminium sprocket carrier which John machines up so that you can still use the stock rear conical hub, but play about gearing on the rear sprocket. Mark has gone the standard 50 to a 47-tooth item, to hopefully allow higher cruising speeds. He thinks it may now be geared a bit high, but the compensation should be smoothness.

LP Williams also supplied their basic oil pressure gauge kit, with the gauge itself sourced off a Mini. The original single saddle was replaced twice, after an unfortunate incident involving the pattern seat which Ron Moss had originally fitted. The bike was running erratically, and with the engine firing, Mark has the points cover off — one unimproved area is that the T160 is still running on its brand new points rather than electronic ignition.

‘The carbs were flooding too and suddenly — WHOOF! — we were on fire. I doused it quick but it had singed the seat a bit.’

Speaking of the carburettors, Mark, in anticipation of fitting a set of the T150/Rocket 3’s less restrictive raygun silencers, had altered the slides to a richer 3.5, but considered changing them back to 4s in view of a certain lumpiness. He also felt that the standard rubber-mounted footrests, wide and low, restrict the ground clearance and so would go for LP William’s rear-sets in future — tourer or not!

When I rode the T160, Mark had put in less than a dozen miles on it after its re-assembly. So I was feeling both privileged and intimidated as I mounted up, started on the button and wound my way carefully out of town. This was a unique opportunity to savour a near-new example of one of the last great motorcycles from the traditional British industry.

When I rode the T160, Mark had put in less than a dozen miles on it after its re-assembly. So I was feeling both privileged and intimidated as I mounted up, started on the button and wound my way carefully out of town. This was a unique opportunity to savour a near-new example of one of the last great motorcycles from the traditional British industry.

First impressions were mixed. The engine, not unnaturally, felt very tight and in truth a bit rough. There was some vibration at lower speeds, that’s in the 40s, in third and fourth; the shakes came through the seat, there was no problem with the rigidly-mounted handlebars. The left-mounted gear pedal for the 5-speed box felt awkwardly close to the engine at first, although the change was acceptable.

Before very long however, a more positive T160 feature couldn’t help asserting itself — the handling had all its usual excellent, making even a nervous rider feel full of confidence and élan. There are very few bikes which make me go back to roundabouts for a second and third go, tilting all the way over and round before pulling smoothly up and away, but this was one of them. And the thoroughly sorted brakes were very good, fairly sensitive but powerful when needed, another source of reassurance.

And a relatively necessary one on this ride, as the flat countryside offered two options, boringly bland by-passes or poorly surfaced B-roads connecting isolated villages. And since this was Fenland, the penalty clause for missing some of those byways’ abrupt and often unsigned changes of direction was to end up in the deep water-filled dykes which had caused them. Anchors on!

Like the Saudi policemen, after stopping to take notes I found that, with the bike having stood for several weeks previously, the electric start ran out of poke after about three goes. No problem; with a little choke via the handlebar-mounted lever, the Cardinal kickstarted first time, every time thereafter.

Running up through the gears I was reminded how little clearance the T160 clutch possessed; it was in or out, and the source of a potential clonk if not used thoughtfully. Neutral was a little fiddly to find when at rest, but it could be done, though the neutral light was u/s. After 20 miles another Trident feature began to be apparent — the seat’s padding was not the greatest.

I began to think what impression a new T160 would have made on a potential buyer back in the 1970s, and had to be a bit dubious about that. Not only the seat and the rather harsh suspension (which no doubt both needed a certain amount of running-in), made one question whether this bike would have made a good tourer — which is how the last Cardinals, complete with their crash-bars, spotlights, Craven panniers, air horns, etc, were marketed back in ’77. I was tempted then, I can tell you, but at £1500 they were way too dear.

For with all the allowances made for its brand-newness the motor had ‘periods’, and plenty of them, where it felt happy or unhappy. Basically it liked a rising throttle (yes, in the end it was a Triumph at heart!) and the responsiveness then was its nicest feature, with the promise of much, much more to come. But it didn’t seem to like going at steady, slowish speeds. There was a transmission snatch if you got the gears wrong, and on those B-roads you had to keep changing up or down, like a Jap bike.

All this was in contrast to the Trident’s natural rival, the Commando, which despite its 100-plus potential could be hoiked into the top of its four speeds and left there all day, always ready to respond to a crack of the wrist. Still, the way Mark had the Cardinal set up meant that top gear felt quite well chosen and you could stay in it — but only if you didn’t mind losing the edge.

Engine noise was negligible, and with 4000rpm on the wavering rev counter, oil pressure was a healthy 60psi. But despite its oil cooler, after 20 miles or so the T160’s brand new engine felt quite hot.

Mark felt that any roughness would be sorted by the No4 carb slides plus some further tuning. I have no doubt he’s right, and I also feel that he’s a worthy and appropriate keeper for this soulful survivor — because he’s manifestly a hard, fast rider, and what the T160 needs, eventually, is Big Welly. Because underneath its copper’s uniform, this Son of the Desert was, is, and always will be a wailing, whooping, Son of a Bitch!

Ex-police? Helpful with enquiries or throw away the key? What do you think?