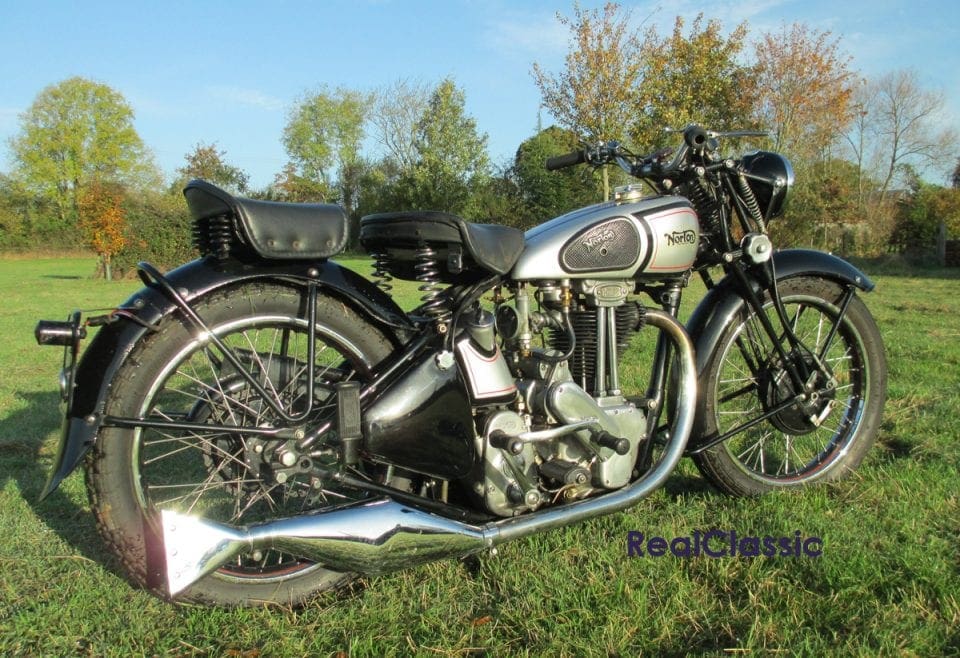

The price of pre-war British bikes frequently puts them beyond most budgets, but the first bikes built after WW2 offer an affordable alternative. This 500 single was manufactured by Norton in 1946 and it retains many vintage virtues, as its owner explains…

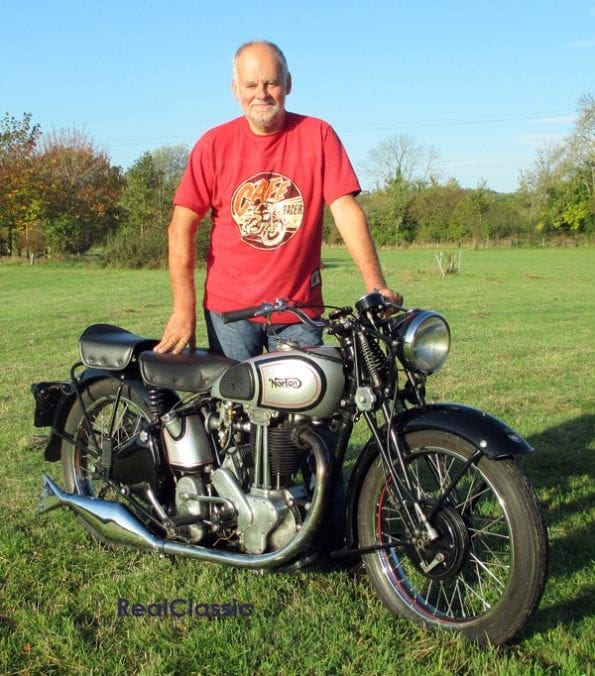

‘It just oozes character,’ grins owner Brian. ‘I’ve owned other girder-fork machines over the years but never a Norton of any kind in 50 years of motorcycling. Although it looks like a pre-war bike, this was actually an interim model produced mainly in 1946 using parts from the 1939 Model 18, just to get production going after the war. From 1947 onwards this model had telescopic forks, a different gearbox and many minor different parts including the handlebar controls. I like the classic, pre-war style of the Model 18 and the silver and black finish – so I just took a fancy to it and bought it a couple of years ago in pretty much the same condition it’s in now.’

Enjoy more RealClassic reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Norton’s big singles can be traced all the way back to the 1920s when the firm’s first ohv 490cc model was designed under the watchful eye of James Lansdowne Norton himself. The new motor used the 79mm by 100mm layout of the Norton sidevalve engine to create a world-beating Brooklands record breaker, which also took to the TT track and scooped the honours in the very first Maudes Trophy of 1923. That ohv single spawned a series of sporting successors during the 1920s and 30s.

Norton’s big singles can be traced all the way back to the 1920s when the firm’s first ohv 490cc model was designed under the watchful eye of James Lansdowne Norton himself. The new motor used the 79mm by 100mm layout of the Norton sidevalve engine to create a world-beating Brooklands record breaker, which also took to the TT track and scooped the honours in the very first Maudes Trophy of 1923. That ohv single spawned a series of sporting successors during the 1920s and 30s.

Then when the ohc Manx racers and their International roadbike counterparts arrived, the Model 18 became a practical touring machine which shared the upmarket livery as competition machines. The 18 was joined by the higher spec ES2 in 1928, and throughout the 1930s the 18 inherited engine and frame developments a year after its upmarket counterpart. The big news for 1937, for example, was ‘a new system of valve enclosure’!

Plans to overhaul the singles in 1940 were postponed when war broke out. The Model 18 was one of the firm’s first bikes to surface on the post-war scene. In 1946 it was reintroduced with a full cradle but still rigid frame, as seen here, keeping its girder forks and with the motor much as it had been at the end of the 1930s. The ES2 returned in 1947 with ‘modern’ plunger suspension, and both 500 singles were given long Roadholder telescopic forks that year. The change to tele forks wasn’t universally appreciated at the time; compared to girders they were felt to limit the amount of steering lock and restrict manoeuvrability, with snubbers needed to stop the fork shrouds clipping the petrol tank on tight turns.

Although most of his motorcycles are later bikes with more advanced suspension, owner Brian hasn’t found it especially hard to adjust to the girder forks up front. ‘Rigid / girder bikes are good fun,’ he says. ‘As long as you let them move about a bit on corners and watch out for deep pot holes they will get you home safely. However, the girders can be expensive to put right if worn, and worn forks really effect the handling.’ Brian deliberately opted to buy an incarnation of the Model 18 which harks back to the vintage era – if that’s a bit extreme for your tastes then the later versions may prove easier to live with.

Bert Hopwood modernised the Norton single-cylinder engines for 1948, paying particular attention to the top end, and introducing numerous detail changes to give the 18 and ES2 more torque and less chatter. The valve gear, piston skirt, flywheels pushrods, magneto sprocket and top end lubrication were revised, and a new one-piece rocker box fitted. This gave around 21bhp at 5000rpm which equated to a top road speed of just under 80mph but – probably more important to the man in the street – the engine noise, particularly from the top end, was minimised.

Nortons also understood that their pre-war gearbox, an evolution of an earlier three-speed, hand-change device, wasn’t suitable for the sophisticated 1950s, and eventually replaced it with their new laid-down gearbox after making-do with various short-term solutions. Brian reckons this is something to check if you’re looking at a 1946 example like his. ‘The gearbox mountings top and bottom can fracture if they have been allowed to run loose. 1947 onwards bikes have a different box.’

Other areas worth investigating include the frame. ‘If there are any signs a sidecar has ever been fitted, check the frame very carefully for alignment. Then things like handlebar controls are pre-war and very hard to source. The best advice is to buy the best example you can and make sure you know the correct specification of the bike. If you pay reasonable money for one of these and later parts have been fitted you will struggle to find the correct parts because so few were manufactured.

‘Basketcases are not for the faint hearted – it’s always better to have let someone else spend the money before you buy the end result. My ideal is an original machine (not a bike rebuilt to standard, which is quite different), but these are few and far between now. I never restore genuinely original bikes like that but just sort them out mechanically for safety reasons. It’s also well worth joining the Norton Owners’ Club. Lots of advice on their website and they run a spares scheme.’

‘Basketcases are not for the faint hearted – it’s always better to have let someone else spend the money before you buy the end result. My ideal is an original machine (not a bike rebuilt to standard, which is quite different), but these are few and far between now. I never restore genuinely original bikes like that but just sort them out mechanically for safety reasons. It’s also well worth joining the Norton Owners’ Club. Lots of advice on their website and they run a spares scheme.’

So did Brian need to do much work to the Model 18? ‘Just servicing, so far. I bought from Chris Spaett at Venture Classics who I have always found a pleasure to deal with, and it was a well-sorted bike. Not concours but tidy and useable, and there’s been no mechanical mishaps to date.’

During the decades when British bike riders became obsessed with high performance sportsbikes, the Model 18 and other old-fashioned long-stroke singles fell out of favour. They were relatively heavy and definitely leisurely, ‘not really about flashing acceleration and high speed,’ as historian Roy Bacon explained. ‘The heavy flywheels, relatively small carburettor and mild cam timings worked together to produce low down torque and pulling

power. The machines were able to carry riders in a relaxed manner at a respectable average speed, they were little troubled by hills and ran around the bends with no need to slow down. On the roads of the time they covered the ground at a faster gait than was apparent and without the rider having to work hard to achieve this.’

Those virtues are now back in fashion, it seems. Brian is happy to ride his Model 18 for miles: ‘it’s surprisingly comfortable as the forks are in good condition. Bouncing along on the sprung saddle and with an unstressed engine at a steady pace, it’s good for decent distances. By this point in its life, the 18 was a well-developed bike. It doesn’t need any modern modifications or technical upgrades if you use it as it was originally intended. It’s a classic British big single: handles well, with decent brakes for its time. Just accept it for what it is and don’t try and ride it like a sports bike!’

——–

Words by Brian Howell and Rowena Hoseason

Photos by Brian Howell

Advert

Enjoy more RealClassic reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more RealClassic reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.