Despite inhabiting a world of perpetual ups and downs, they keep our wheels going round and around. Pistons, says Frank Westworth, are the unsung heroes of the classic biking world.

For some arcane reason which is now beyond me, a friend and I were discussing pistons. I know, I know; the very idea of actually claiming to have friends is a minor puzzle in itself, and wasting quality friend time on matters as dull as pistons does seem a tad eccentric, but there we are. I do have at least one friend, and at a recent point the topic of our intercourse was pistons, the reciprocating heartbeats of most engines. Almost all engines, and almost certainly your own engine, unless you are also afflicted with the rotary fascination, in which case you should cease reading now. Although some misguided souls pretend that rotors are a form of piston, the simple truth is that they’re rotors, nothing less.

Enjoy more RealClassic reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Pistons can be a problem. They can be a particular problem if there are no more new old ones – NOS or new old stock – available for the machine of your choice. My friend had decided, for some reason which doubtless seemed like a good idea at the time, possibly while in a state of wild inebriation or after connecting his brain cell to mains voltage for a while, to inflict a rebore upon his treasured and favourite engine. I have no idea why people do this. I understand the alleged purpose – to restore new vim where vim has departed – but I’ve observed so many dire results of what was once a simple operation that I now live in some hope that I’ll never need to do another simple rebore.

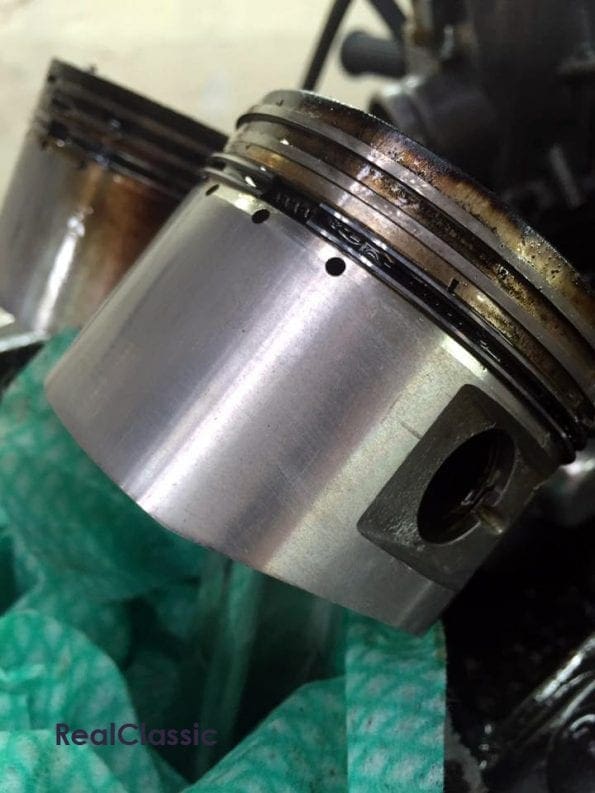

My friend, plainly a fellow of vast good taste, at least in motorcycles, had taken his cylinders to an engineer of repute and familiarity with the world of ancient engines, and had asked this stout swain to do the job. Said boring person accepted the gig, did the boring and supplied beautiful shining new pistons, which my friend, being a dab hand with the spanners, fitted almost at once. His anticipation was obvious, not least because he talked about it, emailed about it, and possibly composed sonnets to the greatness which would be the experience of riding his most bored of bikes. And then he fired it up and rode it. It was horrible. Rough and vibratory. Even more than most parallel twins. He wept baffled tears through the ethers at anyone unfortunate enough to share Facebook with him. It was grim to witness, never mind share. But sharing is what the internet is for, and we get little choice in the matter.

He asked me for advice. I suggested that he have the barrels sleeved and bored back to whatever size suited his old pistons. He was outraged. Possibly horrified. For a brief and glorious period I hoped that his grief and his outrage would demand that he never again mention pistons in my presence, me being a noted dullard when it comes to pistons.

Sadly, however, he asked for my reasoning. So I told him a story. A sort of parabolic story. Less parable than … you get the idea.

Many years ago, I had a friend I’ll call Geoffrey. He was of course called Geoffrey, such are life’s little ironies. Geoffrey rode an Ariel. With the wit of youth and great intellect, we called it ‘Geoffrey’s Ariel’. They were simple days. He thrashed the poor thing mercilessly. He was famous for his instinctive understanding of the exact moment at which a functional engine would transform itself to shrapnel. This understanding was born of repeated experience. Geoffrey had aspirations to Kawasaki Z1 performance, but a wallet which stretched only as far as a very tired Ariel Huntmaster. He went on to design aero engines for Rolls-Royce. I still occasionally worry about flying.

However, his fine engineer’s sympathies enabled him to whip in the clutch just as the Ariel seized for the last time, and shortly afterwards, walking being as tiresome as it is and dosh being elusive, he acquired a set of plus-60 pistons for his Ariel. He was a student engineer at the time, and in between the wild parties and endless debauchery for which mechanical engineers are famous, he found time to knock the seized, scored and burned pistons from his cylinders, discovered that they were the original items and that the bore was standard and had a wheeze, as engineers are also prone to do. So I’m told.

He bored his cylinders to plus-30, and turned the plus-60 pistons down to match, then fitted them, happy in the knowledge that his quest to make his Ariel faster than a Z1 would be inevitably successful.

The bike seized again after about a mile. Plainly it needed careful running in. He ran it in for a painful 500 miles, after which it seized only every hundred miles or so, unless he gave it more than quarter throttle, in which event it seized at once. This is because pistons are not round. They are oval. They are oval for a reason. Engineers know that reason. It is to do with expansion. I am delighted that Geoffrey went on to design jet engines which famously lack pistons.

My more recent friend wondered what this had to do with his horribly rough twin, which was not seizing, but which was unbearably too rough to ride. Nothing, is the answer. His bike is horrid because it is now using pistons intended for a FIAT car and which are completely the wrong weight for his motorcycle engine. But the principle is the same. He should re-use his original factory-fit pistons in fresh bores and all would be well.

Except that he had thrown them away. Like you do…

Photos by Richard Negus, Mike Powell and Ace Tester Paul Miles

Advert

Enjoy more RealClassic reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more RealClassic reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.